Mixed Migration: Traders, Diasporas and Returnees

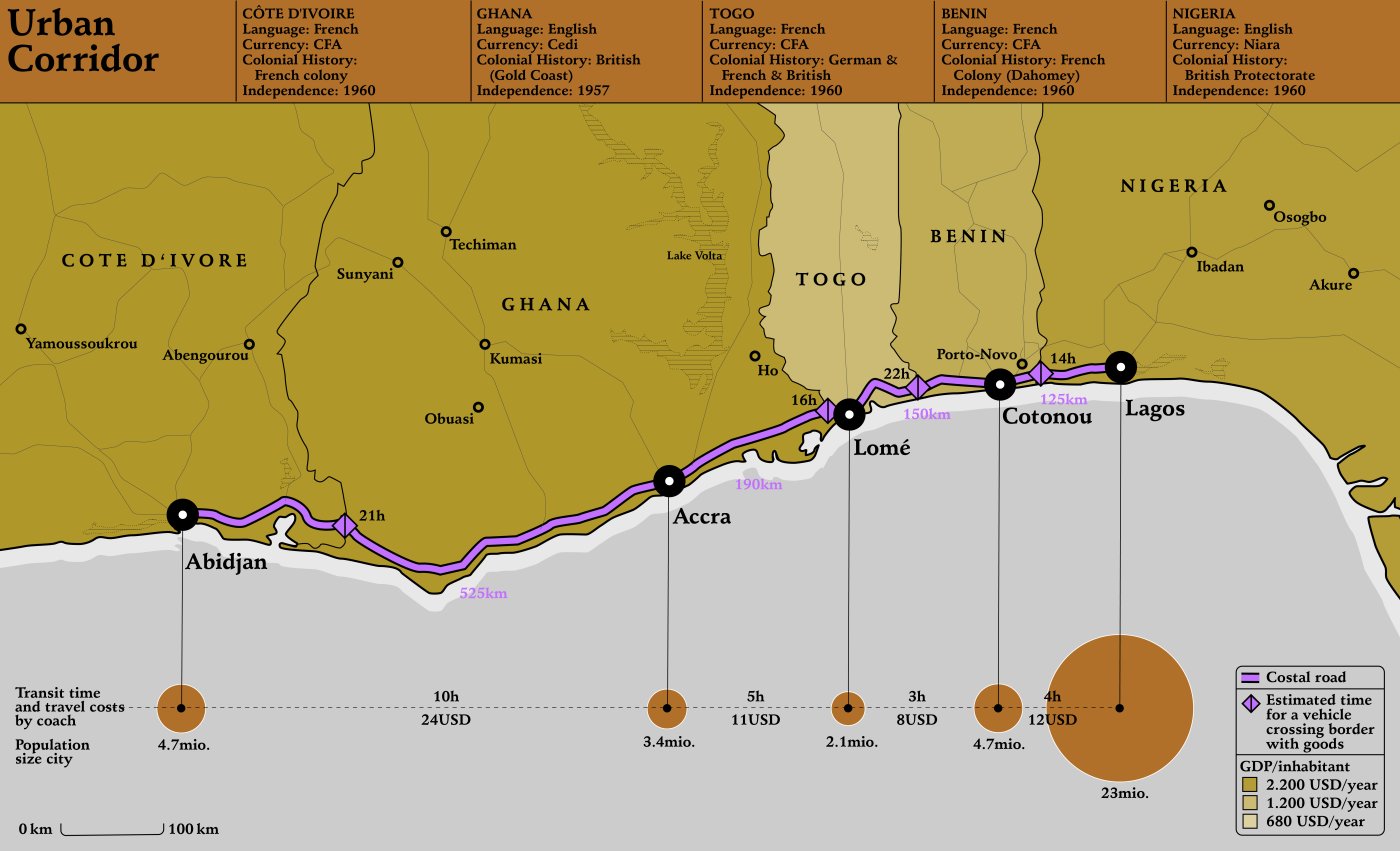

Along the Lagos-Abidjan corridor people are on the move for all kinds of reasons. Some are could be labeled refugees, economic migrants, seasonal workers or international students. Instead of splitting people on the move into various categories, another approach is to adopt the notion of ‘mixed migration.’ This reflects how migrants are never just economic migrants or asylum seekers, but their lives and trajectories are often a combination of both.

For the IOM, “the principal characteristics of mixed migration flows include the irregular nature of and the multiplicity of driving factors such movements, and the differentiated needs and profiles of the persons involved.”1 These are “complex population movements including refugees, asylum seekers, economic migrants and other migrants.”2 Many of these movements are circular migrations and fluid displacements between countries, and even within countries that can be either temporary or long-term.

The classic definition of a migrant is a person who is older than 15 years, who has lived for more than one year in a country where they are not nationals.3 Along the Beninese section of the Lagos-Abidjan corridor the most representative group of migrants in this category, that is to say international migrants, come from the neighbouring countries of Nigeria, Togo and Niger. There are also international migrants from Europe, the Middle East, India and China that in numbers represent very small groups, even if these groups hold significant economic power. International migrants also live and word side by side with internal migrants, which refers to people who have moved from one area of the country to another for the purpose of establishing a new residence.

Many international migrants along the corridor are organised within trading diasporas, for example the Igbo second hand clothes traders or the Lebanese second hand car traders. They are organised in networks, associations or communities that maintain links with their homelands. This concept covers more settled expatriate communities and second or third generation migrants. At times, such migrants have acquired nationality from either the host country, or third country. For example, many Lebanese residing in Benin have Ghanaian passports.

There is a great disparity in the movements and circulations taking place along the corridor. Yet it is exactly the accumulation, and intersection of these movements that is transforming the urban fabric along the corridor. The important takeaway here is that migration can be conceived as a far wider range of movements that rural-urban relocation, and includes a diversity of categories: international or internal, trading diasporas or returnees.

Many scholars are choosing to adopt ‘mobility’4 or ‘movement’ rather than ‘migration’5 as their lens of analysis. This thesis brings together mobility and migration within the same analytical framework. Indeed for authors like AbdouMaliq Simone it is the overarching category of movement, as a process that “has given shape to African cities and regions”.6 This echoes the work of Caroline Melly an anthropologist working on Senegal, to bring together within the same frame of analysis both migration and mobility. Moving through the city, is “as much about what it means to be part of, to move through, to inhabit and construct the African city as it is about the desire and imperative to mobilise labour capital and knowledge on national and global scales.”7 Packaging together the analysis of migration and mobility, Caroline Melly writes of mobility as an enduring, elusive and collective value, that both embodies expectations of migration, and exceeds the binary geographies of arrival and departure. It could be argued that, in comparison to Senegal, this is even more the case along the Lagos-Abidjan corridor. For whilst Senegalese migration is traditionally more anchored in routes to Europe, migration along the Lagos-Abidjan corridor occurs along the same roads as everyday urban mobility.

This positioning is also inscribed within current research trends in the European context. Researchers working on the ‘migration-mobility nexus’ in Neuchatel, Switzerland are seeking to bring together these two categories of analysis and of practice, focusing on the interplay between these two ways of framing movement.8 This approach questions how and why mobility are bound together, asking if they are exclusive conceptions of movement, or if individuals navigate between mobility and migration contexts. In the West African context it would appear that the fluidity between these two concepts is greater.